2022 III SDG Report

Executive Summary

Insurers can tap into new opportunities as both risk underwriters and as investors to support the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of globally shared social and economic expectations, which are increasingly being used by both insurers and corporations across a wide range of sectors as a guiding compass for developing their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) strategies. However, insurance’s potential role in achieving SDGs and advancing ESG more broadly has been underestimated, particularly for broader climate and sustainability initiatives.

Created by the United Nations and adopted by 193 countries, SDGs capture some of the most crucial and formidable challenges for governments worldwide. The SDGs were initially envisioned as plan for countries and NGOs, but it has become clear that success requires collective action across government, civil society, the private sector, communities, and individuals. As the private sector began to take an active role in tackling mission-critical areas– infrastructure, climate change, food security, health, education, etc.-- the door has opened for insurance to support SDG progress as underwriters by transferring risk, as investors, and as corporate citizens.

Insurance is integral to the multi-sector partnership and there is increasing business opportunity for the insurance sector to work with government and private sector clients to develop solutions. However, data remains key to guiding and demonstrating the value of insurance in the achievement of the SDGs. The industry can also better demonstrate this value if it can produce consistent global data by line of business and by investment class to show the contribution to the SDGs. More involvement of the insurance sector in high-level strategic discussions around sustainable development can enable more data curation and develop new business opportunities to provide governments and private sector companies that are focused on the SDGs.

The role of insurance, however, is multifaceted and includes strengthening household and business resilience and facilitating the flow of capital. Looked at from different angles, research shows that insurance contributions move the needle toward SDGs, but the industry is not sufficiently recognized as an integral component for achievement.

This report highlight which SDGs insurance can most contribute to and how that impact would come about. This report covers1 the SDGs from three angles.

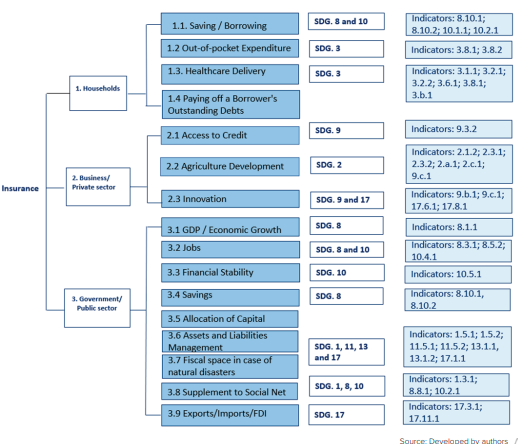

First, the view from the transmission mechanism of the impact of insurance through households, businesses, and the public sectors.

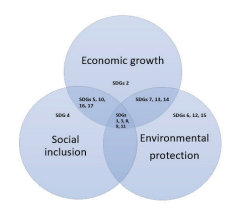

Then, the impact on SDGs is considered through the dimensions of economic growth, social inclusion, and environmental protection.

Finally, the point of view of an insurance company is taken with an examination of how insurers can support the SDGs through underwriting and risk transfer, as an investor and as a corporate citizen/employer.

SDG indicators are data driven but lack a global insurance component.

It has long been believed that insurance has an important role to play in the achievement of the SDGs. There has been some research on this topic, but it has typically been either at a very high level (e.g., GIZ, 2017 2; Swiss Re, 2017 3 ), or alternatively very specific, based on analysis of discrete insurers’ contributions to SDG (CISL, 2019; Allianz, 2019). Research to date has mostly focused on the broad understanding of SDG goals, rather than on their actual components. Given the worldwide relevance of SDGs and the commitment of countries to track progress annually by 2030, insurance supervisors, regulators and investors recognize the need for clear links between insurance and development goals.

The 17 SDGs5 are broken down into 169 targets and 231 unique indicators, which are incorporated into the SDG Indicators Database. Targets specify the goals and indicators represent the metrics by which the countries aim to track whether these targets are achieved. Each target has one or more indicators. The indicators were developed by UN agency expert group on SDG indicators called the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDGs Indicators (IAEGSDGs). They were agreed by UN statistical commission and adopted by Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) on General Assembly. The global SDG Indicators database6 is accessible to investors, regulators, and supervisors. The development of the SDG database is an ongoing process, currently representing 208 geographical areas over the 2000-2019 timeframe. Data is updated annually or once in two or three years and sometimes there is a delay in reporting, so that countries have outdated statistics. Governments can develop their own national indicators to assist in monitoring progress.

SDG indicators do not capture insurance metrics – and global insurance data overall is lacking. Insurance was mentioned only once in Target 8.10. Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance, and financial services for all. However, the indicators under this target do not measure the expansion of access to insurance services (by way of contrast, the number of commercial bank branches, number of automated teller machines, the proportion of adults with an account at a bank or other financial institution or with a mobile-money-service provider are all measured).

Global insurance data is also lacking. Only broadly aggregated life and non-life data are available pro bono on a global basis. Apart from allowing for the establishment of links through each SDG, the lack of disaggregated data is a challenge for supervisors and regulators in measuring and tracking the insurance impact on sustainable development goals overall. Analysis in this report underscores the need for global insurance disaggregated statistics and open access.

Insurance is a key ingredient in a complex recipe for progress.

Countries with high levels of insurance penetration have made the most progress in meeting their SDG commitments – as measured by the SDG index7 . As a starting point for the analysis in this paper, countries’ progress towards the SDGs was compared with their level of insurance market8 . The SDG index score can be interpreted as the percentage of SDG achievement. A score of 100 indicates that all SDGs have been achieved. Figure 1 shows that countries with higher insurance penetration have achieved greater progress in SDG implementation, while countries with lower insurance penetration have achieved less9 , but the SDGs have also been criticized as having a strong GDP or income bias.

However, on closer examination, the relationship between SDG progress and insurance penetration is not solely explained by a country’s income level.

The Sustainable Development Report (2020) reveals that high income countries are not on track to achieving environmental goals (SDGs 12-15) and, by contrast, the bottom countries of the SDG Index ranking perform better on many environmental SDGs (due to very low levels of consumption and production), but they are quite low on SDG (1-9), that represent poor access to basic health services, water, sanitation, and other infrastructure. Classic ‘S-curve’ analysis also shows a more nuanced relationship between insurance market development and GDP – rising particularly sharp at certain levels of average income, see Figure 2 (Enz, 2000).The ‘sweet spot’ between insurance market potential and SDG achievement gaps is examined later in the paper.

7 The SDG Index measures a country’s total progress towards achieving all 17 SDGs . SDG Index and Dashboards that assess progress are published annually by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network and the Bertelsmann Stiftung as part of the Sustainable Development Report. This is not an official SDG monitoring tool, but instead complements the efforts of national statistical offices and international organizations to collect data on and standardize SDG indicators. 8 The insurance penetration rate is the ratio of insurance premiums underwritten compared with a country’s GDP. 9 There is ample evidence of a general correlation between insurance penetration and GDP growth, although the range of impact differs depending on the methodologies and scope of different surveys. For example, empirical evidence from (Lee et al. 2013) suggests that for OECD countries, a 1 percent increase in life insurance premiums raises real GDP by 0.06 percent per year. Covering a larger set of 77 advanced and emerging economies for the period 1994–2005, (Han et al., 2010) find that a 1 percent increase in total insurance penetration led to a 4.8 percent increase in economic growth per year (versus a 1.7 percent increase in economic growth per year when only considering life insurance). 10 https://sdgindex.org/reports/sustainable-development-report-2020/

Figure 3: Transmission Mechanism of Insurance Impact and SDG Indicators

Figure 4: Insurance Contribution.

Insurance contribution towards SDGs is multi-faceted

The insurance sector’s contribution to the SDGs was considered: (1) through underwriting and risk transfer; (2) as an investor; and (3) as a corporate citizen /employer

Underwriting and risk transfer: insurance serves to finance the rebuilding of properties after a loss, pays for needed healthcare, protects the individual from financial loss in the event of accident and assures lenders that if the mortgaged property is lost or destroyed the repayment of the loan will still be made.

Investor and asset manager: insurers, on the asset side of their balance sheets, can contribute to the sustainable development agenda. Insurance companies are significant institutional investors, providing financing to the real economy through investments in green, sustainable, impact bonds, clean energy assets, resilient infrastructure, integrating environment, social and governance (ESG) factors in asset allocation and stewardship activities.

Corporate citizen and employer: insurance companies employ agents and company representatives throughout the world. Corporate citizenship refers to a insurers’ responsibilities toward society. The goal is to produce higher standards of living and quality of life for the communities that surround them.

While all three of these contribution areas are important, currently the role of insurance companies as underwriters who can transfer and mitigate risks stands as the most significant. Each SDG indicator (out of 231) was assessed using these three lenses.

Based on a literature review of previous studies, recent empirical evidence on the contribution of insurance to development outcomes, an analysis of case studies in selected countries, and a review of World Bank insurance market development projects, the potential impact of insurance on each SDG was estimated using a scoring scale: limited impact – 0; moderate impact – 1; strong impact – 2; significant impact – 3, with the scores averaged for each goal. The authors note that there is clearly judgment involved in these assessments (which would benefit from further econometric studies to support) – but propose that this analytical framework gives an overall picture of the potential for insurance to impact SDGs.

Table 1 shows a summary of the SDG where it is proposed that insurance has the most impact. The SDGs where insurance makes a strong or medium impact will be discussed in detail in the next sections of these report.

SDGs where Insurance has a Significant Impact

Climate Action (SDG 13)

Financial and human losses from natural disasters have increased significantly in recent years. According to the 2020 SDG report11, climate change continues to exacerbate the frequency and severity of natural disasters, which affected more than 39 million people in 2018, resulting in deaths, disrupted livelihoods and economic losses. Natural disasters affect every part of the world. In 2019, 409 natural disasters occurred in the world, including 158 floods and 114 severe weather events, 33 tropical cyclones and 32 earthquakes (Aon, 2020)12. In 2019 catastrophic events (including natural disasters and man-made) totaled USD 146bn of which USD 96 bn was insured per Swiss Re Sigma (2/2020). Some man-made disasters, such as fires, are also related to climate change. Increased drought, and a longer fire season are boosting wildfire risk.

Natural disasters can have a sizeable fiscal impact on the most vulnerable economies, often holding back economic growth and poverty alleviation (WB, forthcoming). The indictor Direct economic loss attributed to disasters to GDP appears in three goals (Goal 1. No poverty, Goal 11. Sustainable cities, Goal 13. Climate action13). A recent assessment by the IMF (2018) shows that these macroeconomic impacts can create a vicious cycle that lowers growth and increases debt. On the expenditure side, governments often bear a significant part of the costs of response and recovery. On the revenue side, impacts on the productivity of firms, household incomes and economic output can dent tax revenues. In the aftermath of a disaster, financial decision makers find it difficult to allocate limited resources among many priorities. If decision makers do not have access to sufficient resources to finance disaster response, they rely on outside assistance. In countries that are geographically or economically small and not diversified in economic activities, where key sectors are dependent on weather conditions, the effects of disaster shocks on national economic activity and production capacity can be significant. For example, countries reported disaster losses were up to 4 percent of GDP in Colombia, and up to 2.6 percent in Madagascar (14-year average). Economic loss after disasters can be up to 200 percent in small island states. For instance, Grenada suffered losses of 200 percent of GDP following Hurricane Ivan in 2004, Dominica faced losses 225 percent of GDP after Hurricane Maria in 2017.

Insurance can play a role in mitigating the after-effects of natural disasters on economic growth, and even providing an economic stimulus for a few years after the event. The econometric study of Von Peter et al (2012) shows that small and low- to middle-income countries suffer more when uninsured but also recover faster when insured against catastrophes. Countries with developed insurance markets suffer less from disasters in terms of GDP decline (Figure 5). Countries with smaller insurance markets contract more. Direct economic losses of USD 23.6 billion were reported

Figure 5: Direct Economic Loss, % to GDP, 2005-2018

11 https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2020/goal-13/ 12 https://www.iii.org/article/spotlight-on-catastrophes-insurance-issues 13 Direct economic loss attributed to disasters to GDP (Indicator. 1.5.2/11.5.2) indirectly belongs to SDG 13. Climate action through Indicator 13.1.2 and target C of the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030 (Sendai Framework). Sendai Framework was adopted by UN Member States in March 2015 as a global policy of disaster risk reduction. It outlines seven global targets to be achieved by 2030, five of them (Targets A-E) correspond and contribute to three SDGs (SDG 1, SDG 11, SDG 13) and strengthen economic, social, health and environmental resilience.

by 63 countries, of which 73 percent (USD 17.1 billion) were recorded in the agricultural sector and 16 percent (USD 3.8 billion) in the housing sector. As these countries may not have the funds or borrowing capacity to recover promptly from natural disasters, risk transfer to insurance markets can be particularly effective as insurance can provide relief to governments, companies, and households in the event of natural disasters (Brassard and Raffin, 2011). This may be both directly in the form of paying claims, or indirectly if the local or federal government buys insurance and can then pass on compensation to companies or individual households.

In addition to paying claims, insurers can help promote higher standards of construction by having minimum requirements to be able to access insurance and /or build back better clauses. This can also encourage construction to be in less risky areas. Insurers can work also with governments or private companies on disaster risk management plans, such as evacuation procedures, which will reduce loss of life.

There are, however, some issues which can make it challenging for insurance to have impact on disaster protection. First, natural catastrophes and some other weather-related events are often excluded from property insurance policies. This means that the insured must buy separate cover, but this may not be available or affordable. In emerging markets, natural disaster insurance coverage remains limited. According to a 2005 Munich Re study, only 1 percent of households and businesses in low-income countries, and only 3 percent in middle-income countries, have catastrophe coverage, in comparison to 30 percent in high-income countries. The industry needs to develop ways to close the protection gap in this area, by bundling with other products and / or by public private partnerships like Flood Re in the UK, or Japan Earthquake Reinsurance.

In most developing vulnerable countries, capital markets are undeveloped and the ability to use insurance risk transfer instruments, such as derivatives and catastrophe bonds, is limited. When international financial institutions and other development partners offer various forms of support to disaster-vulnerable countries, many countries have limited capacity to take full advantage of such support (IMF, 2019). It often takes a long time until financial aid become available, which can delay disaster recovery and reconstruction (WB, 2019). Thus, in these countries, people will continue to cope with catastrophic risks by relying on family and community support systems.

Local insurance companies may partner with reinsurance companies in providing protection against a catastrophic loss where reinsurers pay part of the losses and allow the local insurers to remain solvent. The main barrier to obtaining reinsurance for low- and middle-income countries is the lack of primary-market insurance penetration and the current inability in such countries to package reinsurance programs in structures that are attractive to the global reinsurance market (Cummins and Mahul, 2008).

In addition to their underwriting role, insurance companies can also have an impact on climate change though their role as major asset owners. Insurance companies are big investors with USD33 trillion assets under management in 201814. As investors they have a lot of influence whether as buyers of government bonds or as investors in real estate, corporate equity, or debt securities. As such, they can also channel capital to investments that are more climate resilient as well as investing in green assets

Safe Cities and Communities (SDG 11)

Much of the discussion about climate is also relevant to the role insurers can play as underwriters and investors in relation to cities and communities. Insurance companies exert an indirect influence on the resilience and sustainability of cities through encouraging consumers and businesses to use climate-related mitigation strategies (fortified homes, mileage-based insurance, low-emission vehicles, green building, and equipment, etc.) by incentivizing them by offering lower premiums or coverage that would otherwise be unavailable

In addition, insurance companies have an important role to play in supporting infrastructure projects as both underwriters and investors. The capacity of large insurers and reinsurers to underwrite long tenor credit risk is an important factor in supporting infrastructure development (IFC, 2018). In many cases it is easier for insurers to support these projects as underwriters than as investors. This is because illiquid assets and particularly securitized structures often carry high capital charges. Insurance companies which underwrite long tail have liabilities which they want to match in terms of duration and currency and could invest more in infrastructure, alongside DFIs, if capital requirements were less onerous for certain types of structures.

Additionally, insurers, reinsurers and brokers have considerable risk management expertise and can partner with technology companies who can apply AI to aerial photography and satellite images to help risk assessment and mitigation and Internet of things (IoT) data to make cities safer. This can be used to monitor traffic congestion or water quality. This is strongly linked to climate risks in many cases, but the role of insurance is less well developed, and it is less easy to monitor due to the lack of consistent disclosure or indicators.

Insurance so far has focused more on compensating for loss after the event. Ideally, insurance should use allocation of risk bearing capacity and differential pricing to encourage governments, businesses, and households to take preventative measures to reduce the likelihood of losses. Examples include building standards to withstand high winds and raising the height of the ground floor. Insurance can contribute to loss prevention through the provision of risk information, premium discounts for hazard mitigation, or using early warning systems. This is particularly relevant because several of the SDG indicators relate to deaths, missing person, and injuries after disasters. Only a preventive approach will contribute to an improvement in those indicators.

Motor accidents have significant human and economic costs, especially in developing countries. The leading cause of death among people aged 15-29, road accidents kill 1.25 million people every year and injure another 50 million—more deaths than from malaria or tuberculosis. The severity of this challenge is recognized by specific road safety targets (SDG 3, Target 3.6.): to halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road crashes by 2020. The insurance industry is already playing an important role in the road safety agenda. The industry insures almost 1 billion vehicles globally, helping to reduce the costs of road crashes to society and the economy and providing for medical care for injuries, which, in developing countries, are often to pedestrians. Where motor insurance can take account of driving behavior, whether by “no claims discounts” or “bonus malus” systems, or by more sophisticated technology that can track driving on a real time basis, insurance can incentivize and reward safe driving.

Good Health and Well Being (SDG 3)

The role of insurance in health depends very much on the organization of healthcare provision which differs by country. In some countries the government plays a much larger role, but there are still likely to be gaps which can be filled by the private sector. At the other extreme, there are countries with little to no government-funded healthcare, or it may only be available for those at the very bottom of the pyramid. Insurers can support SDG 3 by helping to facilitate access to healthcare through the provision of health insurance. Health insurance can potentially reduce the burden on both government and private citizens, but it is often challenging to deliver in an affordable way outside of company schemes, and, in some countries, there is a shortage of doctors, hospitals, medical equipment and supplies, or quality pharmaceuticals. Nonetheless, insurance can help by providing access to services such as telemedicine and support for preventable diseases using self-diagnostic devices, wearables, tests, and exercises on mobiles etc. We also believe that insurance can help make access to healthcare more inclusive by focusing on the needs of women, self-employed, gig workers and micro-, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), who have typically not been well served by the insurance industry.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shed light on the vulnerability of health systems worldwide. It is clear, that countries with universal health coverage (UHC) defined as all people having access to healthcare without suffering financial hardship (SDG 3.8) are best equipped to respond. UHC data captures two interrelated dimensions: service coverage15 (SDG indicator 3.8.1) and financial protection (SDG indicator 3.8.2). Even when medical services are available, people sometimes incur a heavy financial burden to use them and often must forgo using health care altogether due to high costs

Strengthening health financing is one of targets of SDG (Target 3.c) and critical for reaching UHC. Insurance catalyzes healthcare delivery, by providing a payment stream to secure such services. In many countries, a high proportion of medical expenses are still met out of pocket. It is estimated that nearly 90 million people were pushed into extreme poverty (that is, below the international poverty line of USD 1.90)16. Due to the lack of insurance, health care costs often force those affected and their families into deep poverty. Personal out-of-pocket expenses are higher in countries with low insurance penetration. Nearly 40 percent of the world’s population has no health insurance or access to national health services (ILO, 2020). An estimated 1 billion people will spend at least 10 percent of their household budgets on health care in 2020, the majority in lower-middle-income countries. Most of these people were in South Asia (54 million), followed by East Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. The income loss due to COVID-19 lockdown measures will exacerbate the situation. In developing economies, 11 percent of adults reported having borrowed for health or medical purposes in 2017 (Demirgüç-Kunt A., et. al 2017).

Research also shows that health micro-insurance helps to reduce out-of-pocket health expenditure and increase the use of healthcare services (Radermacher et al. 2012). Levine and Polimeni (2014) in an Indian study find a 44 percent reduction in treatment costs for serious health incidents once insured, while Gustafsson-Wright (2013) finds a 40 percent reduction in a Nigerian study. Most insurance companies are now required to cover the cost of immunizations and preventive care. The private sector could potentially improve vaccination coverage through insurance schemes (Target 3.b). The challenges of delivering affordable healthcare are great. Biometric ID systems, increasingly being rolled out by governments, are an important step to reducing fraud and enabling the further development of private health insurance

Reduce Inequality (SDG 10)

While the role of insurance in reducing inequality is more difficult to track compared with some of the previously discussed SDGs - the potential is there. Insurance can help reduce inequality within countries by helping businesses and families withstand economic losses due to property damage, illness, injury, or death of a wage earner. Although microinsurance has yet to reach its potential, technology advances are offering ways to underwrite, distribute and manage claims more cheaply and efficiently, and there is increasing focus on this within the industry. Some countries require or offer a separate license for micro insurance, with lower capital requirements. However, this is not universal, so it is not possible currently to monitor microinsurance as a separate line of business. Cross border insurance, such as migrant workers buying insurance for their families back home, as well as insurance policies directly tied to remittances also have a role to play.

SDGs where Insurance has a Strong Impact

No Poverty (SDG 1)

This is such a broad goal that it requires the cooperation of government, private sector, and individual action across a wide range of policies and industries. The main ways in which insurance can contribute to this are in ensuring that people and families do not fall below the poverty line due to events like a flood or fire, illness, or death of a bread winner in the family. WB research (2020) shows that17. Moreover, the indicators of this SDG (specifically under Target 1.5) overlap with indicators of SDG 13. Climate action in terms of number of deaths, missing persons and directly affected persons attributed to disasters (Indicator 1.5.1) and SDG 11 Sustainable Cities in terms of direct economic loss in relation to global GDP, damage to critical infrastructure and number of disruptions to basic services, attributed to disasters (Indicator 1.5.2)

Insurance can ensure business continuity of companies after a loss, preserving employment. This is discussed in more detail earlier in the section on climate. Private insurance can also reduce the likelihood of people having to rely on state benefits. As investors, insurance companies contribute to capital markets which are needed to provide businesses with the funds to grow (and thereby support overall economic development)

As employers themselves, insurance companies can contribute to SDGs. Measures include paying a fair wage and providing benefits to their staff, as well as ensuring that pay equity among employees by gender, race, religion etc. Many insurers and brokers are large companies who also support charitable causes in the local community.

Insurance targeted at women can have a particularly strong impact. The SheforShield report found that the global insurance market for women could grow from USD 800 billion of premiums in 2013, to up to USD 1.7 trillion in 2030, with approximately half coming from emerging markets (Grown et. al, 2017). SheforShield provided a detailed analysis of ten emerging markets: China, Brazil, India, Mexico, Indonesia, Colombia, Turkey, Thailand, Nigeria, and Morocco. These markets are expected to grow 6-9 times, with China and Brazil being the largest markets, and Indonesia and Nigeria expected to see the highest levels of growth. The report expects the largest growth in life assurance, which includes pensions and savings products, which are particularly important for women due to longer life expectancy. Education savings policies have proved popular amongst women customers, particularly grandparents, with benefit of helping keep more children in school or college. Health insurance was also seen as important and desirable, and this will be even more so in the light of the Covid-19 pandemic. Non-life insurance, protecting homes, vehicles and small businesses was expected to grow driven by more single, salaried women and women entrepreneurs.

The development of an insurance sector serving women has other benefits. Research by suggests that women are prepared to invest up 90 percent of their income into their household’s vs 30-40 percent for men on areas such as education, healthcare, and improved housing. This means that their families and communities will also benefit. Increasing women’s insurance coverage can also make them more of an economic driver, by increasing their spending power and supporting the development of private healthcare. The report also found significant opportunities for women to work in the insurance industry, with the multiplier effect of reaching more women customers. The insurance industry can also support women entrepreneurs by helping them manage risks, get access to finance and develop more resilient businesses

Implementing social protection for all (Target 1.3) is one of the targets under this goal in which insurance can contribute. The value of social protection to shield individuals and families from shocks and alleviate poverty has been recognized. Indicators of this target are measured by the proportion of the population covered by social protection systems, distinguishing between children, unemployed persons, older persons, persons with disabilities, pregnant women, newborns, work-injury victims. This target regards to government insurance programs, specifically social security programs. Social protection is necessary because certain risks are difficult to insure privately (e.g., unemployment) and are financed entirely or in large part by mandatory contributions from taxpayers, employers, and employees. These programs provide a base of economic security to the population, and a layer of financial protection to individuals against the long-term financial consequences of old age, occupational and nonoccupational disability, and unemployment. However, social protection coverage can range from close to 90 percent of the population in Europe to less than 15 percent in Africa (ILO, 2017). Resent empirical studies have argued that partnerships between governments and insurance companies may be a useful avenue for providing additional social protection coverage (Janzen et al., 2012). Disability insurance, protecting against loss of income due to disability works, is one example of such complimentary insurance to social security programs.

Insurers are also important providers of pension products which are needed to protect against poverty in old age. IAIS and IOPS (2018) conducted a joint study18 which estimated that the share of total life insurance liabilities related to retirement income and pension products exceeds 50 percent globally (higher in some OECD markets such as Australia, UK, USA, and Spain). Private insurance can also complement social security to support elderly populations via health care, housing, and long-term care. Given demographic challenges, and deficits in many public pension funds, the insurance industry may have a growing role to play in supporting the goal of prevent poverty in old age.

Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8)

The insurance industry can improve economic growth, not only in increasing a country’s GDP, but also by improving financial stability and capability. As previously discussed, insurance can make the economy and enterprises more resilient. Insurers can directly create employment but there is an even bigger effect by ensuring that businesses can grow, offer credit insurance, and facilitate imports and exports. The credit insurance market is estimated at around USD 6.0 billion premium by the International Credit Insurance and Surety Association19. Insurers can also influence their “supply chain” by insisting that their corporate clients meet certain standards in terms of safety, not employing children etc.

Insurers have an important role to play in capital markets due to the large amount of assets they can invest from their balance sheets with USD 33 trillion assets under management. Insurers mobilize long-term savings across the economy and help to provide liquidity through various techniques and tools. This can help develop broader and deeper capital markets. Insurers themselves have strict capital and liquidity requirements. As premiums are received in advance of claims, insurers have proved to be more stable than banks in times of crisis and can provide long term investment capital.

Insurers have potential to help fill the infrastructure financing gap. They can do this both by proving long term credit insurance, and as investors as discussed earlier in Goal 11 Safe Cities. According to estimations by the Global Infrastructure Hub (GIH), there will be a need to invest USD 13 trillion globally in infrastructure projects between 2020 and 2040, which translates into average USD 630 billion per annum. If insurance companies would allocate only 5 percent of their gross written premiums to infrastructure investments, it could cover half of the annual investment gap (WB, forthcoming). However, in some cases, high capital requirements make it difficult for insurers to invest more in infrastructure, real estate, and other illiquid asset classes.

Zero Hunger and Food Security (SDG2)

Insurance has an important role here, which has arguably not yet reached its full potential. As an underwriter insurance can support agriculture, especially with products that cover weather events or crop failure. The support of the agricultural sector to ensure food security is a key element in eradicating hunger. An estimated 25.9 percent of the global population – 2 billion people – were affected by moderate or severe food insecurity in 2019 (an increase from 22.4 percent in 2014). Crop risk poses a serious threat for low-income farming households. About 78 percent of the world’s poor people, close to 800 million people, live in rural areas20 and rely on farming, livestock, aquaculture, and other agricultural work to make a living. Insurance policies provide coverage for loss of production or yield loss due to a change in market price during the insurance period.

Agricultural insurance can complement government contingency funding by transferring some risk to the private sector, reducing its financial burden in the event of disaster, and contributing to macroeconomic stability in the face of weather shocks. The insurance sector can also support food safety with product liability policies that protect consumers and ensure high standard and timely product recall. In particular, new technologies are helping the development of index products which can support smallholder farmers. Insurance can increase access to credit for farmers by making their income more stable.

Data and inclusion: the keys to cracking the contribution puzzle

One of the biggest challenges in assessing the contribution insurance makes to achieving the SDGs is the wide gap between the data as articulated in sustainable goals and how insurance sector data is tracked at national level. It is therefore difficult to assess the true insurance contribution in SDG and the greater role which the sector could play in their fulfillment. Additionally, data may not be comparable between countries, for example on natural disasters. Another issue is that whilst some individual companies, particularly the large international ones, provide a lot of disclosure, these are not available for the industry. Various organizations could play a role in closing these data gaps

To overcome this gap, joint effort is required from many stakeholders at multiple levels. At the local level, the data gaps and time lags in official statistics require investment in statistical capacity. At the international level, the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) - in collaboration with other organizations and networks (e.g., OECD, Sustainable Insurance Forum, Insurance Development Forum) - could play a role in data collection and publication. In its Strategic Plan 2020-2024, the IAIS set a strategy to develop the different quantitative and qualitative information bases to inform the identification and assessment of trends and developments relevant to the insurance sector.21 IAIS, bringing together insurance supervisors and regulators from more than 200 jurisdictions (representing 97 percent of the global insurance premiums), could consider developing a platform for collecting and disseminating globally insurance sector data statistics. As the international standard-setting body, IAIS could also assist with the implementation statistical standards and classification

The following types of data would be particularly useful to cover:

Line of business data. As discussed in this note, different types of insurance contribute to achieving the SDGs. For example, crop insurance will help in achieving target 2.1 (end hunger and ensure access by all people to food), motor insurance target 3.6 (halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents), flood or catastrophe insurance with target 1.5 (build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters). Detailed global data for all major classes will assist in targeting and focusing on specific SDG targets and allow cross-country and regional comparison. In terms of classification, insurance business categorizes broadly into two major classes - life and non-life. The leading suppliers of global insurance market information (for example, AXCO22) provide insurance statistics in three broad groups - life, non-life (P&C) and Personal Accident & Healthcare (PA) worldwide. Non-life data are usually presented in aggregate form. However, the non-life category is broad and includes different types of insurance, such as property, liability, motor, marine, aviation and transit, travel. Sometimes this detailed information is available in country profile dashboards, reports, or national data sources. However, global comparisons can be inconsistent due to different classification, format, definitions across countries. In addition, financial sector authorities in many countries do not disclose all available data to the public, especially when the data related to financial sector soundness and stability.

Asset allocation data. There is no global data on insurers’ asset allocation available yet. As an alternative to global insurance statistics, OECD Insurance Statistics for OECD countries and several non-OECD and EIOPA Insurance Statistics (for European countries) are available. Given the role and scale of insurance sector as an investor, data on global asset allocation is extremely important. The data would help to better understand the asset allocation of insurance companies and reflect changes in investment strategies, considering their potential for “impact investing” and supporting the SDGs as an investor. This would also allow an assessment the direct exposure of insurance companies to certain assets such as housing or renewable energy.

Sex disaggregated data. As discussed, insurance can play a role in supporting women and girls, but there is no data available for the sector broken down by gender. Sex-disaggregated data can contribute to a better understanding of gender considerations in insurance access and usage. This information can be used by supervisors to better target policy and regulatory measures, stimulating inclusive insurance development and uptake. Globally, this data can be used to support broader research and peer learning between insurance supervisors and other relevant stakeholders on the regulatory barriers that hinder women’s access to insurance (A2ii, 2017). The SheforShield report recommends gathering sex disaggregated data, not only on premiums and number of customers, but also on acquisition costs, retention, claims, customer satisfaction and other factors that can further support the development of the market. It also suggests gathering data and conducting more analysis of women’s risk profiles, using information such as income levels, family structure, life cycle events such as marriage or having children, and geography as the need of rural and urban women are vastly different. Insurance supervisors could:

• encourage insurance companies and insurance intermediaries to collect sex-disaggregated data for personal lines classes.

• include gender considerations on access and uptake of insurance in the national financial inclusion strategy.

• develop financial literacy programmes incorporating insurance trainings that consider women’s specific needs and behaviors.

• promote gender diversity in the insurance industry

Governments, regulators, and the insurance industry itself give more consideration to the impact of insurance on the SDGs when formulating policy and strategy. A first step would be collection of data on a global basis that can directly show the contribution of insurance to the SDGs. To establish a starting point, and set a base for monitoring future progress, it is recommended that the industry collects consistent global data on insurance by line of business, a split of insurers’ invested assets and gender disaggregated data

Fostering a dialogue between the regulator and insurers about their role in achieving the SDGs can also have an impact. Insurance regulators can engage through global platforms of insurance supervisors and regulators to strengthen the understanding of sustainability issues amongst the entities which they oversee and the challenges facing the insurance sector, particularly in developing countries, from incorporating these issues and goals into their operations. Regulators should mainstream ESG and SDG issues into the regulatory frameworks, introducing guidance for insurers in developing risk policies targeting ESG and SDG goals, and integrating these factors into reporting.

Conclusion

Insurance companies can significantly contribute as underwriters of risk, investors and asset managers, and corporate citizens and employers. Whereas insurance is explicitly mentioned only in SDG 8, Decent Work and Economic Growth, the analysis for this paper suggests that insurance has an important role to play in helping countries meet several other SDGs, particularly Climate Action (SDG 13), Safe Cities and Communities (SDG 11), Good Health and Well Being (SDG 3), Reduce Inequality (SDG 10), No Poverty (SDG 1), Decent Work and Economic Growth (SDG 8), and Zero Hunger and Food Security (SDG2). Further, insurance has the potential to play a more substantial role in countries where the economy and financial markets are sufficiently developed. Still, it is challenging to assess this due to a lack of data.

As climate and sustainability becomes more of a strategic priority for corporations, many are choosing the frame their ESG goals in the context of the SDGs. This report reveals several crucial opportunities in which insurance can significantly impact SDG goals, indicating that the industry’s role in supporting the SDG efforts of countries and companies has been overlooked. Gauging progress and optimizing future impact requires expanding data collection and study.

However, insurers need a seat at the table to close this data gap and deliver proof of impact with consistent data across the globe. The industry and its corporate clients will likely continue to use ESG strategies in increasingly competitive business environments, and scrutiny of these strategies will increase. Therefore, the complex but worthwhile effort for more data can enable the insurance sector to pursue new strategies for profitable growth and remain at the forefront of economic growth and sustainability in the coming decade.